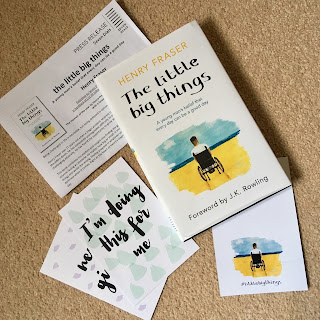

After reading the final page of The Little Big Things, I slowly closed the book and sat alone with my thoughts for a while. It’s not often that I feel divided about something I’ve read; usually, by the time I’m halfway through, I have my thoughts somewhat in order. However, this memoir had me to-ing and fro-ing so much that I went back to the publisher who sent me the book and asked whether they really did want me to be one of the reviewers. After talking to Seven Dials and hedging my thoughts and concerns, they encouraged me to go ahead and post an honest review. So… here we go.

The Little Big Things is the memoir and work of Henry Fraser, an incredibly talented individual who creates impressive works of art using only a mouth stylus. The book tells the story of Henry becoming paralysed after an accident on holiday at the age of 17, and his process of learning to live with his condition and find his new normal. Before I get to the review, I want to make clear that I think Henry sounds like an ace person, and definitely somebody who I’d be friends with. None of my critiques of the book are really a reflection on him.

Since my biggest grievance doesn’t relate to the content of the book itself, let’s get it out of the way first. As important as it is to keep my integrity and share only my honest thoughts on stuff I’m reviewing, being sent a press release from a publisher and criticising the marketing of it isn’t something that I’m at all comfortable with doing. But as a chronically ill person, who has dozens of long-term ill friends and works with disabled people every day, I don’t think I’m alone in being sick to death of the word ‘inspirational’ being synonymous with disability.

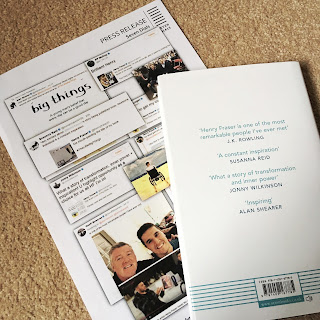

Every single time a disabled person’s story is mentioned within any media outlet, they are presented as either inspirational and heroic, or as needy, weak and vulnerable. There is literally no in-between, and the overuse of the word ‘inspirational’ to me serves to reinforce the idea that you have to do something remarkable for your disability to be valid. And whilst that’s another issue for another time, I couldn’t help but sigh when I first saw that of the eight quotes on the press release, six contained the word ‘inspiration’ in some form. “Okay”, I thought, “let it go this time”. And I did. Until I opened the book and this bookmark fell out:

‘Henry Fraser inspires me because…’. There really is no escaping that pesky little ‘I’ word. To give a really honest opinion, if I saw this book in a bookshop, the marketing alone would have deterred me from buying it. And whilst I’m sure that not everybody would agree, I also don’t feel that I would be alone in this either.

After seeing this marketing, I was expecting to find the story within to be one of the stereotypical valiant kind; of an individual tragically becoming disabled and never once for a second being anything less than 100% positive and full of unicorns and rainbows, and being glad that they became disabled and not changing that fact if given the choice, because it made them the person they are today.

However, bear with me, because I have to say that this story was not exactly that. Henry gives an honest and frank account of his experience of becoming unexpectedly disabled, and for that I want to thank him profoundly. He used this platform to inform his readers of just how difficult his adjustment period was, how badly his mental health was affected by his disability, and how it was tiny, tiny steps forward that brought him to where he is now. He avoided falling into the trap of telling able-bodied people what they perhaps wanted or expected to hear, about an overnight miracle recovery and the aforementioned unicorns and rainbows. Instead, he tells his readers about the reality of his situation, without inducing the need to feel sorry or pity him in any way. The book was conversational, witty and well-written, and was fast-paced enough to hold the reader’s interest throughout. And not once (that I saw), was the word inspirational used by Henry in reference to disability. Just saying.

Despite this, I will admit to having a couple of issues within the content, my main one being the portrayal of determination in relation to recovery. This is where I have to choose my own wording carefully. As a chronic illness sufferer, I know first-hand just how much determination it can take to simply make it through the day. Determination is something that becomes instilled in you as you learn to live within your capabilities, whether you realise it or not, and I agree with Henry that it does play a role in your condition management. However, the wording used in The Little Big Things seemed to imply that determination is inherently responsible for people’s progress and recovery from severe ill-health. And whilst I don’t doubt for a second that determination does play something of a role, I wish it could have been made clearer that in general, determination alone isn’t what brings about a person’s recovery. Whether or not a person recovers or not isn’t related to how determined they appear to be, however much I wish that was true.

To use a personal example that I don’t often share, it was initially my own determination and misguided perseverance to recover from the mild onset of my condition at the age of 15, that led to me becoming so unwell and suffering from the debilitating long-term illness I have now. Obviously, everybody’s experiences of ill-health are unique and incomparable, and there’s no way all of our experiences are going to mirror each other. It’s just that I feel like this book could be one of those that a well-meaning relative or friend uses to point the finger and say ‘if he can do this through determination, why can’t you?’. Believe me, I’ve been on the receiving end of many of these subtle finger points in my time, and it doesn’t half make you feel like a failure. And to be honest, it’s utterly ridiculous to feel like a failure for not being able to cure your long-term physical condition by thinking good thoughts. But I digress. It’s not that any of these things were explicitly mentioned in the content, but I definitely felt like that was the implication that an able-bodied person may take away from this book.

Despite this, it’s important to note that I found that the last chapter of The Little Big Things to really redeem itself, so much so that it left me with an overall positive impression of the memoir. Henry talks about ‘being grateful’ in a way that I wanted to stand up and applaud:

“I suppose because people feel that if I’m grateful and I’m in a wheelchair, they should, on the basis of having their mobility, be grateful for that at the very least. But […] it’s not about comparing what I don’t have to what you do have. That’s far too reductive in my opinion. Being grateful is about looking around, opening our eyes to all the little things we might take for granted. […]

But being grateful can be tiring and overwhelming […]. I would be crazy if I said I was grateful about and for everything”.

He goes on to explain how he wants to use his influence to address wider issues within disability, one being how it feels wrong to him that people seem to be punished for being disabled. He addresses the current benefits system in the UK and how “decisions about disability payments and disability opportunities are made by those who don’t understand what it’s like to be disabled”. Again, I thought this was applause worthy: it takes guts to talk about such a topical issue, and I’m sure it will encourage those who’ve never had to give the benefits system a second thought to pause and consider just how ridiculous the process currently is. I currently work with disabled people, and every day I hear stories about people’s benefits assessments that are so appalling that they’re almost unbelievable; therefore, Henry’s speaking out was particularly welcomed by me. I thought that this last section, and the balance between talking about Henry’s personal positives whilst addressing the wider discrepancies of a society sadly still prejudiced against disability, resulted in a strong and emotive concluding chapter.

To sum up, I had mixed feelings about this memoir. I do wonder, if I hadn’t found the marketing so aversive, whether I would have had more of an open-mind when reading the book. As I mentioned earlier, disability is so subjective that it’s impossible for either this memoir or my review of it to represent the entirety of disabled people, and so I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether or not this book sounds like one you’d like to give a go. If you do want to find out more and order a copy of your own, you can do so here.

Finally, I just want to say that despite all my ramblings, I think Henry Fraser is absolutely ace. He’s achieved so many remarkable things in such a short space of time, and I have no doubt that he will continue to do so. Not only that, but his mouth-stylus artwork is more beautiful and innovative than what most people can create with two hands, and I’ll definitely be looking to purchase something of my own in the future. Take a moment to find out more about Henry and his work before you go, and if you do decide to read the book, I’d love to know what you think. If you have a different viewpoint to my own, I’d particularly like to hear your thoughts. Where do you stand on the use of the word ‘inspirational’ in reference to disability?

Many thanks to Seven Dials (Orion Books) for inviting me to review The Little Big Things, and for being so supportive throughout. If you liked this post, be sure to check out my other (less controversial…) bookish content too!